With the European Championships still three months away, there is already plenty of talk about the legacy of the tournament. That is, experts are warning that Poland and the Ukraine might become the next Portugal. Or South Africa, speaking in World Cup terms.

The case is like this: all these countries got awarded a major football tournament and, lacking the proper infrastructure, invested heavily in building brand-new shiny stadiums. The problem: after the tournament these stadiums lacked proper use, and turned into the proverbial white elephants.

The suggestion is that Poland and Ukraine will also find themselves with eight white elephants after the tournament. The arenas, which came with a heavy price tag, will shine during the Euros, but will become obsolete after, just like so many of Portugal’s and South Africa’s stadiums.

We argue that this likely won’t be the case, and we present five reasons why. But, before we start, let’s first have a look at Portugal.

What went wrong in Portugal?

Portugal won the bidding process for Euro 2004 by beating a Spanish and a combined Austria/Hungary bid. Portugal managed to beat favourites Spain because of the excellent co-operation between the football federation and the government, but also because of a promise to invest in the Portuguese football infrastructure.

The country did not waste any time and duly constructed 10 brand new arenas, more than in any of the earlier tournaments (despite the same number of matches as in 2000 and 1996). Portugal’s two major cities, Lisbon and Porto, both offered two playing venues, with the other eight spread around smaller cities.

The largest stadiums, the two in Lisbon and Estádio do Dragão in Porto, hosted the bulk of the matches, leaving a mere two for every other stadium, including such architectural beauties as in Braga and Aveiro. This would not have been such an issue if those stadiums had found a proper home after the tournament. However, in many cities they failed to attract extra crowds, leaving the clubs and local governments (the owners of the stadiums) with massive maintenance bills.

Right now, eight years later, two of the ten stadiums don’t have an occupant, with the clubs having moved back to smaller grounds. Boavista, which plays at Estádio do Bessa, currently finds itself in the third division, whereas two other clubs fail to fill even a third of their stadiums.

The question now is if the same thing is going to happen in Poland and Ukraine, two countries with a relatively small league, and hardly a reputation for packed football stadiums. What’s more, the countries’ stadiums are even larger than those in Portugal, averaging a capacity of about 48,000, compared to only 37,000 in Portugal.

Still, we don’t think there will be a lot of white elephants. And here’s why:

1. Poland and the Ukraine have the population to back up their stadiums.

Portugal is a country of 10 million inhabitants. Poland and the Ukraine both have about four times as many. What’s more, the Portuguese are heavily concentrated in the country’s two biggest cities (a third of the total population), whereas people in Poland and the Ukraine live far more spread out over the country.

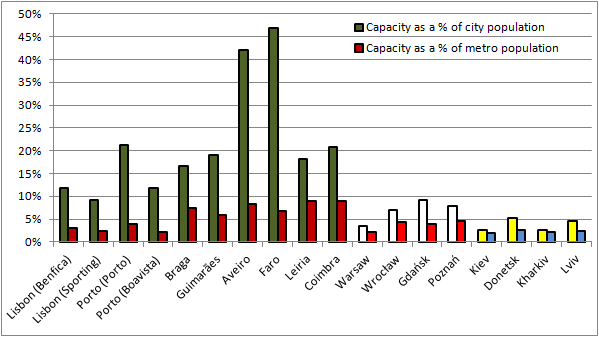

This means, that Poland and Ukraine had more big cities to choose from and did not have to resort to small or medium-sized cities like the Portuguese did. In a chart:

What we see is that the capacity of the Portuguese stadiums was in all cases more than 15% of the population of the city they were located in. In two cases this was even more than 40%. And even in the case of Lisbon and Porto both stadium’s capacities added up to more than 20% of the cities’ population. If taken as a percentage of the wider metropolitan population this is still almost 10% for many of the stadiums.

In comparison, no Polish or Ukrainian stadium capacity makes up even 10% of the city’s population, let alone the metropolitan. Therefore there is way more potential for the stadiums, from a sports (high attendances), commercial (concerts and events), as well as financial (sponsors) perspective.

Population is, however, not perfectly correlated with attendances. Ask the inhabitants of towns like Heerenveen, Hoffenheim, or Lens. Or the fickle Parisians. There is, of course, also football culture.

2. Football is the Big 3 in Portugal. It is more in Poland and the Ukraine.

In Portugal people support one of the Big 3, that is, Benfica, Porto, or Sporting. Whether they live in Lisbon, or outside the city. Few people support a local team, even if there is a decent alternative, and will therefore not quickly go to the local stadium. They prefer to watch Benfica or Porto on television. Which means that there was from the start very few potential for the other Portuguese clubs to increase their attendances.

People in Poland and the Ukraine however tend to support the team from the city they live or grew up in. Actually, most support a team in the Premier League or Primera División. Due to the dire state of Polish football (hooliganism and dilapidated stadiums) there used to be little reason to get emotionally attached to a local football team. However, now facilities are better and hooliganism is on the retreat, someone from Wrocław will support Śląsk, and not Legia or Wisła.

Success in Ukraine is more centralised with Shakhtar and Dynamo having a hold on the championship, but still, someone from Kharkiv will support Metalist, and not Dynamo.

3. Past attendances were already higher in Poland and the Ukraine than in Portugal.

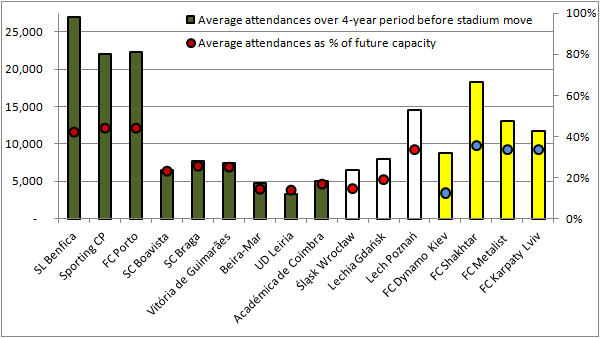

Well, kind of. First the chart:

What we see is that the Portuguese Big 3 already had very decent attendances at their old stadiums, solid in the 20,000s, filling a good 40% of the planned capacity of their future stadiums. There is a certain truth in the saying “if you build it, they will come”, so their new stadium sizes did not seem too unreasonable.

Braga and Guimarães also seemed logical host cities as they achieved significantly better attendances than the other clubs. Alarm bells should have gone off with Boavista, even though attendances seem ok, but it were the club’s heydays (the club even won the Portuguese title), and attendances still hardly increased.

The other three clubs (there is no data available for the Algarve clubs as they played in the lower divisions) did not even average 5,000 visitors a game, only 15% of their planned future stadium capacity. No one could have expected that these clubs were suddenly going to sell out 30,000-stadiums, or even filling half of them.

Ukraine’s attendances, on the other hand, were already very solid. Not at the level of the Portuguese Big 3 of course, but, as they all averaged about a third of their planned future capacity, with enough potential. Kiev is the exception: a small stadium and a city without a real football culture. But it’s the capital, so unavoidable as a host city.

Poland’s selection of host cities seems rather odd though, especially of Wrocław and Gdańsk, as both clubs were struggling on the field in the mid 2000s with long spells in the second division. Hence the far from spectacular attendances, better than the bottom Portuguese clubs, but hardly so as a percentage of the planned capacity. Especially as you consider that Wisła Kraków, from Poland’s second largest city, attracted attendances similar to Poznań. Even Zabrze, home of Górnik Zabrze, seemed more obvious with attendances easily topping 10,000.

So it seems that the Polish organisation committee took a gamble with choosing Wrocław and Gdańsk as host cities. Our next point shows that they may have been right.

4. New stadium attendance have bounced up more in Poland and Ukraine than they did in Portugal.

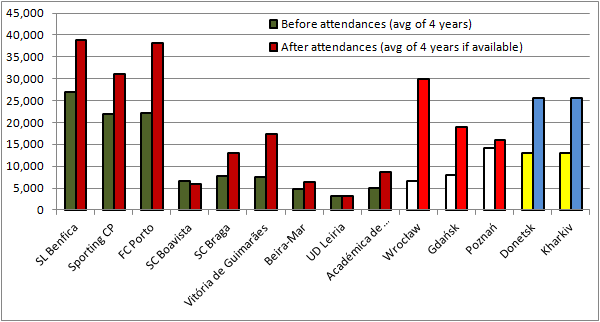

The Polish and Ukrainian clubs that have thus far moved into their new stadiums have shown a lot of promise in terms of attendances.

In the chart we can see that the Big 3 clubs in Portugal have reaped significant benefits from their move to a new stadium. Also Braga and Guimarães have seen their attendances grow to reasonably healthy levels. The problems are, again, with the other clubs. Actually, both Beira-Mar and Académica saw reasonable relative increases in attendances, but they just came from a too low level to make much impact. Boavista and Leiria‘s new stadiums did hardly make an impact.

Ukraine however has already seen very healthy increases in attendances. Attendances for both Shakhtar and Metalist games have doubled. Dynamo and Karpaty have only played one match each at their new stadium, which were very well attended (50,000 at the Olimpiyskiy and 30,000 at the Arena Lviv), but cannot be used for proper predictions.

Lechia Gdańsk has already played half a season at their new home and more than doubled their attendances to just below 20,000. Śląsk Wrocław has only played four league matches at their new stadium and has attracted an average of 30,000 fans (excluding the opening match).

It is likely that averages for both clubs will decline to levels of 15 to 20,000, which is not bad at all. One wonders though why both cities did not opt for a capacity of around 35,000, like the Arena Lviv and Metalist Stadium.

Lech Poznań has not seen that much of an increase in attendances, but they came from decent levels anyway, and will likely improve again when the team’s performance on the pitch improves.

After the initial bounce of playing in a new stadium, attendances tend to stabilise quickly, and there is little evidence to suggest that they will decline again in the long-term. Though a club’s successes on the pitch will obviously have some influence on attendances, this tends to average out over a long-term period.

Stadion Narodowy in Warsaw is the only stadium without an occupant as Legia Warsaw decided to built their own new stadium. It will however be Poland’s principal concert venue (with Coldplay and Madonna already scheduled for the summer), and will also generate significant income from conference facilities and the rental of office space.

5. Football in Poland and the Ukraine is undergoing a broader development.

The eight stadiums that have been built for the Euros aren’t the only ones that have been built in the countries in recent years. Legia completed the construction of its 31,000 Pepsi Arena two years ago, and Wisła Kraków the redevelopment of their Stadion Miejski only a few months ago.

Other, smaller, stadium that have been built in Poland in recent years include the 16,000 Stadion Zagłębia Lubin, the 15,000 Stadion Cracovii, and new stadiums in Kielce and Gdynia. A 30,000-stadium is currently being built in Zabrze.

Odessa, in the Ukraine, has just seen the official opening of the 34,000 Chernomorets Stadium, and the Dnipro Arena, in one of Ukraine’s other major cities (Dnipropetrovsk), has already been in use for a few years.

In both countries football is developing beyond the Euro 2012 stadiums, whereas this was spotty at best in Portugal with the rest of the league never really taking off in terms of modernisation.

Conclusion

It is probably save to conclude that Portugal massively overeached with building 10 new stadiums. Estádio do Bessa and Estádio Municipal de Leiria should never have been built, and it would have been wise to construct the Estádio Algarve, Estádio Municipal de Aveiro, and Estádio Cidade de Coimbra in such a way that they could have gotten scaled down to capacities of 15 to 20,000 after the tournament (and built Estádio Algarve closer to the city).

On the contrary, there is no doubt the Polish and Ukrainian stadiums will serve a purpose after the Euros. One could argue that the capacities could have been a bit more modest (though football fans were complaining about this in efficient Austria and Switzerland), and questions have also been raised about the price tags of some of the stadiums.

It is however unlikely that these stadium will turn into white elephants (save disastrous club management), and more likely that we are going to see a lot more of Polish and Ukrainian football in the future.

© Photo Aveiro: Wikipedia user Nuno Tavares.

© Photo Braga: Flickr user LeonL.

© Photo Gdańsk: Flickr user Mateusz Skuza.