Last week we compared the attendances of Europe’s major leagues, and now we take the opportunity to zoom in on each of these leagues, starting with the Premier League.

In our previous article we concluded that average attendances in the Premier League are second in Europe only trailing the Bundesliga, that stadiums are very well-filled with over 92% of seats sold (similar to the Bundesliga), that more than half of all matches were sold out, and that there were four teams selling out all their matches and four teams selling out none.

We also saw that the attendances of Premier League teams were very stable, in fact, the most stable of Europe with generally few fluctuations. There was a bit of a slow start, but they moved up nicely toward the holidays fixtures and then again toward the end of the season.

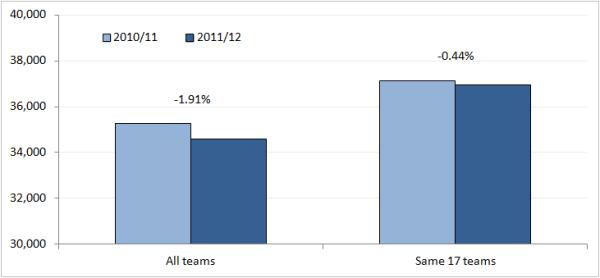

Before we start giving you a break-down per club, let’s first make a quick comparison with last season. On the left the difference in attendances if we look at all teams in the league:

If we look at this chart and notice a decrease in attendances of almost 2%, we might be inclined to write alarming headlines and wonder what is going wrong with English football.

However, that would not be completely fair. After all, the 20 Premier League teams of the 2011/12 season are not the same as the 20 of the 2010/11 season. Birmingham, Blackpool, and West Ham were relegated and replaced by Norwich, QPR, and Swansea, and those latter three tend to attract on average less fans than the former three.

So when we look at the 17 teams that played in the Premier League in both seasons (in the chart on the right), we see that the decline has been very small and hardly significant. It is the good old stable Premier League again, though that doesn’t mean that there aren’t any teams with problems, which we will see later.

First of all, the ranking of this season’s averages by club:

There are few surprises at the top of the ranking as many of these clubs tend to sell out most matches and attendances merely reflect the capacities of the stadiums.

At the bottom of the ranking we see that QPR had the lowest average followed by Wigan, Swansea and the two relegation strugglers from the north-west of England. In the defence of QPR and Swansea it has to be said that they have been the only two of these five teams to have regularly sold out matches.

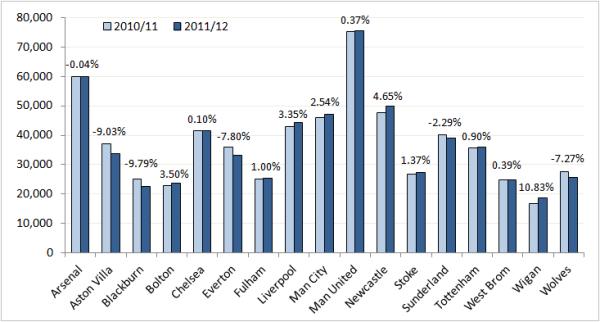

More interesting though are the differences in comparison with last season.

Man United, Arsenal, Chelsea and Tottenham were already selling out most matches and have continued to do so. Manchester City have made the leap from now-and-then selling out to rather consistently selling out.

Liverpool fans have been more loyal this year than the last. Whereas last season attendances dropped quickly after a poor run of results, this season Anfield kept selling out until much further in the season. Crowds only decreased in the last few home matches.

Newcastle has seen the clear results of their great form and attracted almost 5% more fans to the St James’ Park. The only club that recorded a double-digit growth was Wigan though. The club tends to get a lot of stick for their poor crowds and one may argue that the growth comes from a low base, but an 11% growth is impressive nonetheless.

At the other end of the spectrum we encounter a few clubs that are the almost opposite of Wigan and recorded a decline in attendances of nearly 10%. These clubs are Blackburn, Aston Villa, and to a slightly lesser extent Everton and Wolves.

Wolves have got an excuse though as Molineux had a reduced capacity due to the redevelopment of the Stan Cullis Stand. The problems and negativity surrounding Blackburn this season have been well-documented and clearly had their effect on enthusiasm.

Aston Villa had a very poor season, but Everton did just fine and one may assume that the club’s fans have gotten used to the team’s slow start by now.

To get a better perspective of these average we need to see them as a percentage of the stadium’s capacity, that is, how well do the clubs fill their stadiums? Let’s refer to this as the occupancy rate.

We already mentioned that while QPR’s and Swansea’s attendances averaged amongst the lowest, they do have very decent occupancy rates. Their problem is mainly that their stadiums are very small, though from that point of view one can argue that QPR’s rate of 94% is not even that impressive.

Blackburn has done worst in filling their stadium, followed by Wigan and Aston Villa. These were the only clubs that were not able to sell 80% of their tickets, which leads us to the general conclusion that occupancy rates in the Premier League are just very good.

Which also does not come as much of a surprise as most of these clubs possess modern stadiums that were often downscaled when they got built or redeveloped back in the 1990s and 2000s.

To complement the picture we have the number of sold out matches per club, or to be more precise, the number of matches that had an occupancy rate of at least 97%.

There are very few surprises here, possibly apart from the fact that even the likes of Man United and Liverpool could not attract enough people to sell out Villa Park, Ewood Park, the Reebok Stadium and the DW Stadium.

Another analysis we made is to look at how attendances developed over the season. As putting 20 teams in one chart would get a little messy we have split them up in the ten with the least up and down movement and the ten with the most movement.

First the boring ones with the least movement:

There is few what catches the eye here, perhaps apart from Liverpool’s slight dip in attendances around the end of the season. Most of these club had relatively few movement of attendances. One could say that these have the most loyal fans, however that would be a bit rash to do so on the basis of only one season and if you are operating close to full capacity you automatically have little movement.

Man United and Arsenal had the least movement of all, in both cases the standard deviation of the movements was less than half a percent, which means that for any next match one would not expect a movement up or down of more than half a percent.

These clubs were followed by Norwich, Spurs, Man City and Chelsea with all standard deviations just over 1%.

The next chart of the clubs with the most movement gives a whole different picture:

What we see is a clear performance effect at Newcastle, where attendances moved up significantly after fans got the idea that it might turn into an exciting season for them. Wigan attendances also seemed to move up as soon as the club started on a good run of results toward the end of the season.

Most of the movements, however, do not seem to have been caused by performance, but more so by the opponent or just plain randomness. We do see that most clubs recorded their highest attendance at the end of the season, often their last home match, with the exception of Wolves who had of course already been relegated by then.

One could argue that these clubs have the most fickle fans, but again that would not be fair to do so on the basis of just one season. Still, if we want to make the ranking, we see that Bolton Wanderers had by far the most fickle fans this season. The standard deviation of the attendance movements suggests that they are expected to go up or down by 17% from one match to the next.

Bolton is followed by Blackburn, Everton, Wigan, and Sunderland with all standard deviations of over 10% (Everton was the only of these five that recorded a standard deviation lower than 10% last season. Bolton was again top of the list).

Now we’ve looked at the past, one might also want to think about the future. What’s next for the Premier League?

Let’s first look at the short term, that is, next season. If we look at the teams that have relegated, Blackburn, Bolton, and Wolves, we are talking about the numbers 13, 16, and 17 of the attendance ranking with an average of about 24,000. These will be replaced by Reading, Southampton, and West Ham United.

Taking into account this season’s attendances of these clubs and the ones they had in their last season in the Premier League it would not be unreasonable to expect an average of 30,000, which is significantly higher than that of the relegated ones. Which means attendances should move up next season.

If we talk about normal growth, we come across the problem that the Premier League already operates at 92% of capacity, which means opportunities are limited. It therefore mainly depends on the likes of Villa, Everton, Newcastle, and Sunderland how attendances will develop. If these teams have good seasons, they will likely move up, but it is also not unreasonable to expect that the decline of Villa’s and Everton’s attendances will continue next season.

In the long term growth will therefore have to come from expanding the stadiums of teams that are currently at full capacity. Swansea has the most concrete plans to expand the Liberty Stadium to 30,000 seats, while Fulham and West Brom are looking to go to a similar number by adding about 5,000 seats to Craven Cottage and the Hawthorns. It is however far from sure that all will play for regular sold out houses with increased capacities.

Norwich has stated to only consider expanding Carrow Road after having played for three consecutive years in the Premier League, while Stoke seems to have abandoned plans for expanding the Britannia Stadium.

Real growth will therefore have to come from the three big teams that are currently looking to build a new stadium or redevelop an existing one: Chelsea, Liverpool, and Spurs. Plans we have regularly reported on. In all cases this would result in capacities ranging from 55,000 to 60,000 and it is not unreasonable to suggest that they would be able to fill these on a regular basis. The plans of Manchester City to expand the Etihad Stadium to over 70,000 seats are currently too vague to seriously take into account.

So if we assume the most positive scenario and imagine planning permission and sufficient funding for all these clubs to execute their stadium plans, then we look at a long term average of around 41,000 to 42,000 fans per game, which would be a very decent increase of 20%, but insufficient to really challenge the Bundesliga.