The Primera División’s attendances are arguably one of the most interesting of Europe. Few clubs regularly fill their stadium, so there are quite a few fluctuations. What’s more, we had quite a contest between Barcelona and Real Madrid on who would have the highest average this year.

We already know from our general comparison of Europe’s major leagues that the Primera División averaged 28,676 spectators per match last season, making it the third best-attended league of Europe.

We furthermore found that the Spanish clubs managed to sell just under 73% of all seats, and that only 10% of all matches were completely sold out. Attendances were also very volatile, often fluctuating heavily from one home match to the next.

But before we start our in-depth analysis, we first need to remark that collecting Spanish attendance figures has been no easy exercise. There are no official data published, and we therefore depended on the figures that Spain’s major newspapers published. Unfortunately, these newspapers regularly managed to report several completely different figures, making a bit of interpretation necessary.

As a check, we have compared our figures with those of european-football-statistics.co.uk, and found most to be very much in line, in fact, often surprisingly similar. We are therefore confident that our numbers are reasonably accurate, but bear in mind that they are rough numbers.

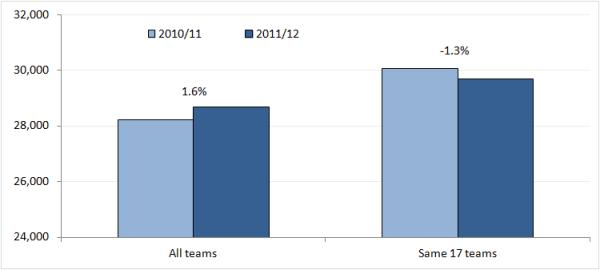

We start our in-depth analysis with the comparison of the 2011/12 average with that of the season before:

We see here that the average increased with 1.6%, which is decent, but these numbers of course include three new teams that replaced three relegated ones. And one of these promoted teams was Real Betis, which has reasonably large attendances.

So if we take out the six relegated and promoted teams, the small increase turns into a small decrease of 1.3%. However, not a decrease to really worry about.

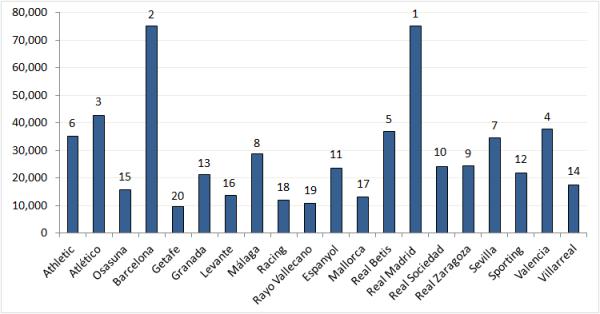

The next chart will answer the question whether Barcelona or Madrid had the highest attendances last season:

The answer is Real Madrid, but only just. After the big 2 there is quite a gap to the rest of the field where we find the likes of Atlético, Valencia, Betis, and Atheltic. Kind of the clubs we expect there to be.

The difference is large between the top and the bottom, because Getafe does not even attract 10,000 people per match, and Rayo Vallecano and Racing de Santander hover only just above that.

If we compare the individual club attendances of the 2011/12 season with those of the previous season, we get the following chart:

Over half of the clubs had an increase or decrease of 5% or more in attendances, and six clubs had a difference of more than 10%. Most of these differences seem performance-related. Levante and Málaga both had exciting seasons, and Zaragoza had a great rally at the end of the season that prevented them from relegating.

Espanyol and Mallorca both had uneventful seasons, and Racing and Villareal relegated. The odd one out may be Getafe, who long challenged for European football, but saw a decline in attendances of more than 13%.

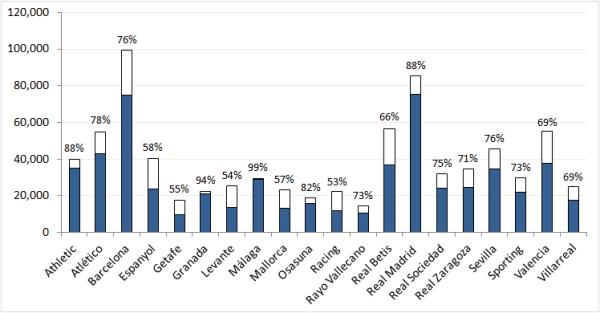

The next chart shows how well the clubs were able to fill their stadiums:

Málaga and Granada did really will in filling their stadiums, and also Athletic had a respectable 88% occupancy rate. On the other end of the spectrum we have the clubs with poor attendances that often play at too-large stadiums.

It is striking that many of these clubs with poor occupancy rates play in stadiums that are relatively new. Sure, Getafe’s Coliseum Alfonso Pérez and Mallorca’s Iberostar Estadio are lacking in many ways, but Espanyol’s Estadi Cornellà-El Prat is a fine stadium and it seems that the Espanyol board somewhat overestimated the club’s fanbase when it decided to build a new stadium with a capacity of over 40,000 seats.

If we look at the number of sold out matches, we see that only Málaga and Granada sell out on a regular basis. Both clubs sold out just over half of their home matches. No other club managed to sell out more than three home matches, and seven clubs did not sell out even one single match during the season.

Normally we would now show how attendances developed over the season, but due to the earlier mentioned reporting issues, we do not think showing individual data points gives a reliable picture. Instead we will show you a different chart:

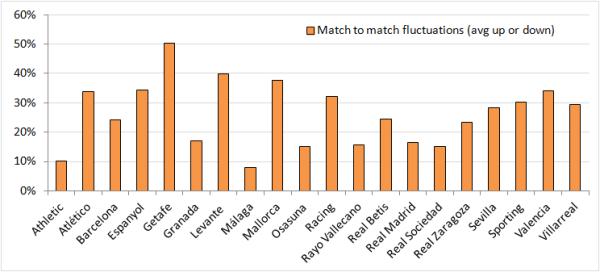

The above chart shows you how much the attendances typically moved up or down from one home match to another (in statistical terms: the standard deviation of the movements).

Getafe showed the most movement. From any home match to the next attendances moved up or down with as much as 50%. The fans of Levante and Mallorca also proved to be particularly fickle.

The fans of Málaga and Athletic were the most loyal. Granada’s fans would have joined them if it were not for one significantly lower attendance mid season, which may in fact be a reporting issue.

Real Sociedad’s attendances also proved to be very stable considering they have a lot of free capacity. That said, their 17% was about equal to that of the Premier League’s most fickle fans, those of Bolton.

One thing that causes the high volatility of Spanish attendances is that the home matches against Barcelona and Madrid attract significantly more people than those against the other teams. That is despite the higher ticket prices most clubs charge for the privilege to see Messi and Ronaldo.

So what does the future look like for the Primera División? Will the success of the league bring growth to Premier League levels, or will the continuing economic crisis result in more people staying at home. The fact that the LFP is increasingly scheduling matches at hostile kick-off times like 11:00 pm will surely not help.

Of course, nobody knows what will happen with the economy. What we can predict, however, is whether next season’s attendances will benefit from the return of Deportivo de La Coruña, Celta de Vigo, and Valladolid, who will replace the trio of Sporting de Gijón, Villarreal, and Santander. They will, probably, and in particular La Coruña’s high attendances will pull the average up.

If we look at long-term growth, this could come from new and renovated stadiums, something we have seen in England and Germany.

There are currently three clubs (almost) building new stadiums, which all have a rather high-profile: Valencia, Atlético and Athletic.

Valencia’s and Atlético’s new stadiums are surely state of the art and both clubs have aimed high with capacities of around 70,000. Possibly too high, and it is unlikely that they will be able to completely fill their new stadium right away. Both stadiums are still far from finished though, and in particular Valencia’s problems are well-documented.

Bilbao’s new stadium, on the other hand, seems to be progressing a lot better, and the club has also been more sensible with a capacity of 54,000 seats, which may even be too modest considering Athletic’s loyal support.

The rest of the Primera División stadiums is a mixture of sufficiently decent stadiums, barely acceptable stadiums, and downright poor stadiums, and in most cases there is still a lot of opportunity for improvement in terms of hospitality.

That said, many Spanish clubs have already at some point played with the idea of building a new stadium, for example Zaragoza, Mallorca, Málaga, and Celta, but in the current economic climate few will find the funding.

Madrid does have plans to further expand the Bernabéu, though only with a few thousand extra seats. Barcelona, on the other hand, have recently postponed plans for a new stadium or extensive renovation of Camp Nou.

Something that Spanish clubs might actually be able to do to increase attendances is to lower ticket prices. These are now the highest of Europe if adjusted for purchasing power, and one would imagine that lower prices may convince more people to make the journey to the stadium. Real Betis is said to already consider such move.

While Spanish attendances are still very decent, there remains the feeling that the league has a lot more potential than it is currently showing, and it might not be that unreasonable to think that the combination of returned economic growth and sensible policies of clubs and LFP may bring the league to the levels of the Premier League, though this will likely at least take a decade or two.