There is much to like about the Major League Soccer (MLS) these days. Brand-new soccer-specific stadiums, an increasing number of high-profile international players, lots of American talent coming through, and ever increasing attendances.

The MLS seems finally to have grown into the healthy league it always strived to be, and the best indicator for this are likely those attendances. Like we earlier did with Europe’s top leagues, we have compiled the attendances data of the MLS this season and performed some analyses on them.

The format of this article will be somewhat different though, as the MLS has some peculiarities we would like to further investigate. We will also take a bit more of a forward look to see what the MLS can do to sustain the momentum they have right now.

Let’s start with some basic facts though, which is that the MLS averaged 18,807 spectators per game this season, which ran from March until last week. The play-offs are still in full swing, but we have left these out of consideration.

This average of 18,807 is an increase of 5.6% in comparison with the 2011 season. One of the reasons for this increase was new expansion team Montreal Impact, which started the season with a few very good attendances at the Montreal Olympic Stadium before they moved to the renovated Stade Saputo, but even without the Impact the autonomous growth was a very solid 4.3%.

To put that number into context, this makes the MLS the seventh-best attended in the world (ignoring Argentina and Mexico, which lack reliable attendance data). They have almost reached the same level as the French Ligue 1, though still trail the Dutch Eredivisie and have the Chinese Super League right in their back. The chart in this tweet gives a nice overview.

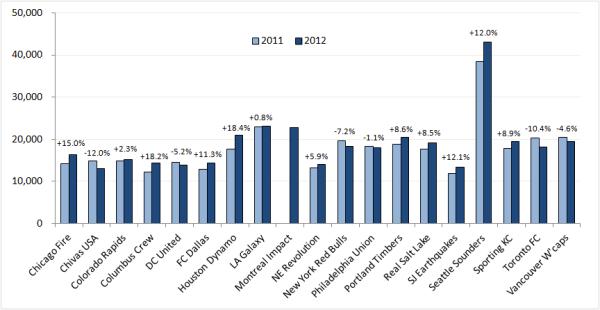

Of course, not all clubs do equally well every season, and surely there are a few clubs with some disappointing numbers. Here is the chart of the individual results:

One of the key characteristics of MLS attendances quickly becomes clear when looking at the chart, which is that there is very little difference in level of attendances between the clubs. In an earlier article we provided a measure for this, which was the difference between the attendance at the 75th percentile and that at the 25th percentile (of all attendances of all clubs). In the case of the MLS, the attendance at the 75th percentile is 1.47 times greater than that at the 25th percentile. In contrast, the equivalent numbers for Europe’s most egalitarian leagues, the French League 1 and English Premier League, are 1.69 and 1.76.

The Seattle Sounders are, of course, the exception. They have attendances almost double those of the number two, the LA Galaxy, and have potential for even more as they play at the large CenturyLink Field. In recent years, they have gradually opened more parts of the stadium for ticket sales, and this season operated with an official capacity of about 39,000. They did, however, open the complete stadium for a few matches, which raised the average to over 40,000.

They are one of tree clubs that play at a stadium that size, though the only one voluntarily. DC United and New England Revolution are still in the same situation in which most MLS clubs were only a decade ago, which is that they play at a much-too-large stadium that was not built for them. They both have plans to build a smaller soccer-specific stadium, though the situation of the NE Revolution is somewhat more ambiguous as their owner (Robert Kraft) also owns their stadium (Gillette Stadium, which is shared with NFL side New England Patriots, the principal occupant).

Good performances on the pitch drove the significant increases in attendances of the Chicago Fire and San Jose Earthquakes, while the Houston Dynamo benefited from the move to the new BBVA Compass Stadium. Toronto FC and Chivas USA had very bleak seasons, so their decreases are forgiveable, though the New York Red Bull’s significant drop should worry the club’s management.

The troubling attendances at the Red Bull Arena have often been blamed on its poor location out of town in the New Jersey suburb of Harrison. On the other hand, the stadium ranks among the finest stadiums in the MLS and the Red Bulls have had a very acceptable season, though petulant behaviour of their stars has somewhat dampened enthusiasm. We will find another reason for their lower attendances later on in this article.

The MLS is actively advocating the expansion of the league with a second team from New York, possibly the New York Cosmos, and hopes a new rivalry may also boost the Red Bulls, though one could just as well imagine that this may further threaten the attendances at the Red Bull Arena.

Calculating occupancy rates is a rather complicated affair for the MLS as various stadiums can be configured with different capacities, some clubs occasionally move to larger stadiums, and other clubs report attendances that are over the official capacity of their stadium.

Still, if we look at the official capacity of the stadiums, then every club managed to fill at least 70% of all seats. The average occupancy rate is 88%, though this drops to 85% if we remove the matches that were played at much larger capacities (mainly Montreal and San Jose).

Special mention should go to the Portland Timbers, as they managed to sell out every single game at Jeld-Wen Field, even though the stadium had been further expanded compared to the 2011 season.

Apart from attendances being rather equal, there is another thing that attracts the attention when analysing the MLS’s attendances, which is that there is a significant amount of up and down movement.

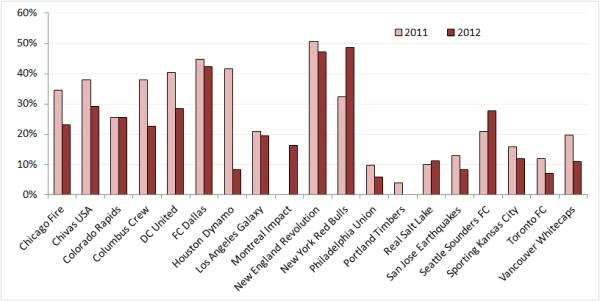

The following chart shows the average up and down movements from one home match to the next:

It turns out that the Red Bull’s main problem is that their fans are rather fickle as from one match to the next attendances moved up or down with an average of 49%.

Over all clubs and the whole season, the average match-to-match up and down movement was 21%, which excludes movements due to occasionally moving to a much-larger stadium.

The average of 21% is rather high compared to the Premier League and Bundesliga, but also to the Dutch Eredivisie, which is very comparable to the MLS. These leagues have averages below the 10%.

On the other hand, this average is significantly lower than that in Serie A and La Liga, but these leagues tend to have the typical upward surges in attendances due to high-profile opponents coming to town, which we discussed in this article. The MLS, however, has much less upward potential due to their high occupancy rates, which means that a lot of this movement is rather random.

Is this a bad thing? Not that much, but it does mean that while the sky seems the limit if it comes to MLS attendances, there is also less of an established floor. This floor is a permanent fanbase that sticks with the club in good and bad times, and while it can increase or decrease, this usually only happens very gradually. The high volatility in the MLS attendances suggests that the permanent fanbase of the MLS clubs is relatively low, and that much of the attendances are therefore made up by more casual visitors.

It is, of course, a great thing that the MLS can attract these casual visitors, but the challenge of the clubs lies in turning these casual visitors into permanent fans. That they are already working on this is proved by the fact that the average up and down movements are decreasing. Last season, the average of all clubs was just over 26%, which has now declined to 21%.

The start of the play-offs was less promising though as much lower-than-average crowds showed up at the first round of matches, stressing that the MLS is still off from turning a definite corner to long-term sustainability.

Another thing that one would expect to happen, is that that there will start to occur more differences in the crowds each opponent attracts. In Europe, most leagues have various teams that attract significant larger away crowds, but in the MLS there is just one team that really draws more spectators away from home, which are the LA Galaxy. The NY Red Bulls were at the same level last season, but seemed to have lost much of their appeal in this one. If it comes to the other 17 teams, differences in appeal are basically non-existent.

This is probably the moment to stress that this analysis has been written from a European point of view. While we follow the MLS and have a decent understanding of other American sports, there might be certain aspects of US fan culture we completely overlook, and if so, feel free to add in the comments (but, please, in a kind way).

We would now like to focus on a few peculiarities of the current set-up of the MLS, which are not that uncommon in other American sports (though not all), but are rare in Europe.

One of the obvious peculiarities are the play-offs, but more interesting is the unbalanced playing schedule, which means that not all teams play the same teams over a season. The 19 MLS teams are divided into two conferences (East and West), and in the 2012 season this roughly translated in each team playing their conference rivals three times and the teams from the other conference once. The result was 17 home and away matches each, but against different teams (which in turn requires a play-off system to keep things fair).

This format was introduced for the 2012 season after playing a traditional balanced format in the previous two seasons (though in earlier seasons different types of unbalanced schedules had already been operated). The reason for this change of format was not so much the addition of the Montreal Impact to the league, after all, 36 matches a year would hardly be unusual, but also to cut travel costs and, more importantly, to highlight the conference rivalries of each team, which in turn should lead to increased crowds and enthusiasm.

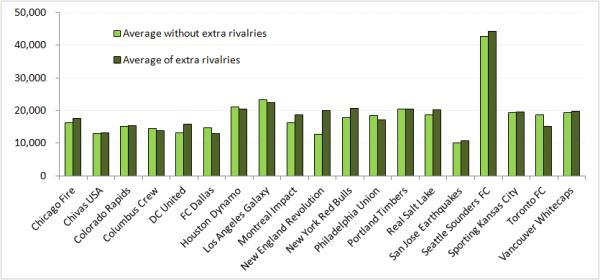

We have tested whether this hypothesis has proved to be true and if these extra rivalry matches have indeed attracted bigger crowds. The next chart shows the difference in attendances between the regular matches and the extra conference rivalries:

Some clubs seem to have benefited from the new format, though for others the difference seems negligible or non-existent. Overall, the average attendance of the extra “rivalry-matches” was 3.6% higher than that of the regular matches, though one should take into account that most of these extra matches were played during the last third of the season, when attendances are naturally higher. While it is hard to give an exact estimate for this, one expect there not to be much difference once this is taken into account.

What’s more, the new format has resulted in DC United, New England Revolution, New York Red Bulls, Philadelphia Union, and Toronto FC missing out on a home match versus the LA Galaxy, the only team that really pulls in some extra crowds. While writing off the new initiative after just one season may be a little too rash, it does appear that the extra rivalries have added very little to crowd enthusiasm.

There is, of course, also the issue of cutting travel, but let’s not pretend that a few more flight hours is a significant burden on well-trained professionals that not uncommonly travel across the country on a day off.

There was something else which attracted our attention while we collated the attendance data, which was the irregular playing schedule. At different points during the season, some teams had played significant more matches than others (easily three or four), and there was little regularity in varying home and away matches. While European fans can expect their side to more or less play a home match every other weekend, this is far from the case in the MLS, and teams may play a series of home matches and then have to wait several weeks for the next one.

This irregular schedule is not uncommon in other American sports, for example in the NBA (basketball) and MLB (baseball), but these teams play many more matches a season and travelling would make a more regular schedule practically impossible. The NFL (American football), on the other hand, where teams play only once a week, does have a very regular schedule of home and away matches and teams can only be one game ahead at any point in time.

The point is that more regular home matches may help turn the casual visitor into more permanent fans. Furthermore, a neat playing schedule in which every team has more or less played an equal amount of matches may create further suspense and consequently boost excitement.

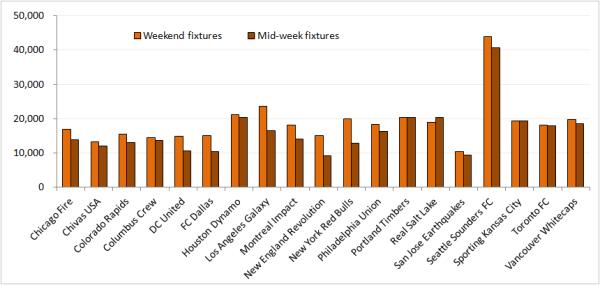

This is merely a hypothesis though and needs to be tested, which we did on one tiny part, which were mid-week matches. While collecting the data, we got the feeling that these mid-week matches attracted significantly lower crowds and we compared the weekend attendances with those of the matches that were played on a Tuesday, Wednesday, or Thursday (ex. US Independence Day fixtures):

There is no denying that mid-week fixtures are very unpopular, and in particular the attendances of DC United, FC Dallas, New England Revolution, and New York Red Bulls suffered significantly when a match was played during the week (at times more than 30% lower).

Not all clubs were equally unfortunate with mid-week home fixtures. Portland Timbers stayed free of mid-week home games, LA Galaxy and Sporting KC also came of lightly with just one, but the Vancouver Whitecaps played almost a third of their home games during the week.

While lower attendances during the week are also the norm in Europe, the differences do seem very large (on average 14% lower), which seems to reinforce the point that still too many spectators are casual visitors that cannot be bothered to go to the stadium on a weekday. The Red Bulls seem the perfect example.

Of course, part of these mid-week games get scheduled there for broadcasting reasons, so just abolishing them might be too drastic of a change. Instead, it might make more sense for the MLS to give the playing schedule more identity. For example, the NFL also has a Thursday and Monday match, but these get moved from the playing round of the weekend. In the case of the MLS, the teams that play on Wednesday generally also play the weekends before and after, and clearly defined playing rounds are hard to distinguish.

The Red Bulls, for example, have played their seventeen home matches on Wednesdays, Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays at 12:00 noon, 1:30 pm, 2:30 pm, 3:00 pm, 6:00 pm, and 7:00 pm. This does not help to either spontaneously plan a trip to the stadium or schedule your other activities around a season ticket.

Let’s be clear though that we are talking about some minor criticism in a generally very positive report. It is probably because of the strength of the MLS attendances, that one feels that they do not need such gimmicks as extra rivalry matches.

The future is therefore bright, and will only be brighter now the San Jose Earthquakes have started building their new stadium. It will take a few more years though before the last of the pack, DC United and New England Revolution, will move to a soccer-specific stadium. Chivas USA have also been considering moving to an own stadium that would better fit the size of their crowds.

That is not to say that all other clubs are already playing at a modern arena as in particular the first generation of soccer-specific stadiums were rather bare affairs. Built-in concert stages also did not improve looks, and the stadium were often located far away from downtown in suburbs, mainly because these offered a better financial deal.

Columbus Crew Stadium, Dick’s Sporting Goods Park, FC Dallas Stadium, and Toyota Park are some examples that suffer from one or more of these issues, and offer a stark contrast with BBVA Compass Stadium, the Red Bull Arena, and LIVESTRONG Sporting Park.

It will take some time though before these clubs will start building new stadiums, and few expansion plans of other clubs exist, which means that attendances are likely going to hit a ceiling in the next few years as stadiums will increasingly be filled to a maximum. The Italian Serie A will therefore remain out of reach.

The measure of success may instead have to be sought in the volatility of attendances, and clubs should now aim to turn casual visitors into permanent fans and reduce the average up and down movements to around 10% per match. Once that number is reached and stadiums consistently sell out, they can then turn their attention to expanding stadiums.

Photo credits: Rio Tinto Stadium – © Flickr user AcousticDimensions, Gillette Stadium – © Flickr user Lorianne DiSabato, Red Bull Arena – © Flickr user AcousticDimensions, PPL Park – © Something Original at en.wikipedia, Stade Saputo – © Flickr user Jay Clark.