The Premier League is the jackpot of football. No other European league rakes in the same amount of money, and no other league divides it that equally. If you are one of Europe’s many mid-sized clubs, the Premier League is where you would want to be.

The problem with the Premier League is, of course, that it only has place for 20 teams, and even though it limits eligibility to English teams, there are easily double that competing for a spot.

So what is the recipe for getting into the Premier League and staying there? It is easy enough to make an educated guess and list such variables as sound policies, effective scouting, being based in a large catchment area, a prolific youth academy, and surely a healthy dose of luck.

Having a rich owner can also propel a club to England’s top league, but if such easy money is not around, it has often also been argued that playing at a large stadium increases the probability of a prolonged stay in the Premier League. The extra matchday revenue and added prestige of a large stadium may be just the extra boost a club needs. But is this true?

There have been relatively few developments in English stadiums in recent years. The activity of the 1990s is well-documented, but developments more or less came to a halt after the opening of the Emirates Stadium in 2006. Since then, only Cardiff City and Brighton & Hove Albion have opened new decently-sized stadiums.

The result is that most clubs now play at a stadium with a size that was determined by their status in the mid and late 1990s, or otherwise was destined by the limits of a pre-existing stadium, but which they now feel is not large enough for permanent Premier League football, which means they may have to increase capacity.

Most of these clubs have something in common, which is that they play at a stadium with a capacity of between 20,000 and 30,000 seats, and feel that they need to expand to over 30,000 seats to be guaranteed of regular Premier League football.

The clubs that are currently very seriously considering expanding are Fulham, West Bromwich Albion, Queens Park Rangers, Reading, and Swansea City. Clubs that have thought of expanding, but have now taken a more long-term view include Stoke and Norwich. Wolves have built a new stand, but for now postponed the rest of their plans. Brighton and MK Dons have also just completed an expansion. Southampton and Forest have vaguer ambitions. Scrapped plans include those of Derby County, Portsmouth, Sheffield United, Birmingham City and Middlesbrough. Bristol City’s new stadium status remains unclear. West Ham’s bid for the Olympic Stadium is another variant with the same goal.

Apart from the above clubs, there are also Chelsea, Everton, Liverpool, and Spurs that have or had ambitious plans, but these clubs are already pretty much guaranteed of Premier League football. Add to these another five or so teams that have a pretty solid Premier League status, and that leaves about 10 places to challenge for.

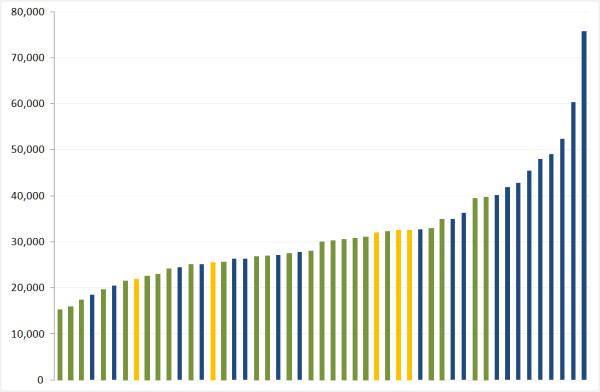

We start our analysis with a chart that gives an overview of the present situation. The blue columns are the Premier League teams, the green ones the Championship teams, and we have added a few other Football League teams that either have played in the Premier League in the last decade or have a stadium with a 25,000+ capacity.

What is particular about English stadiums, is that there are a lot with a capacity of between 20,000 and the lower 30,000s, but relatively few with a capacity higher than approximately 33,000 seats. The big clubs that have already cemented their Premier League status have long broken out of the pack with capacities of over 40,000.

But despite the fact that the nine largest stadiums all house a Premier League club, there are still quite a few clubs with a smaller stadium that have made it to the Premier League, such as currently Swansea, QPR, Stoke, and West Brom.

The thing is, we really cannot consider just one year of data, but have to look over a larger period to find out whether there is a proper correlation between stadium size and Premier League longevity.

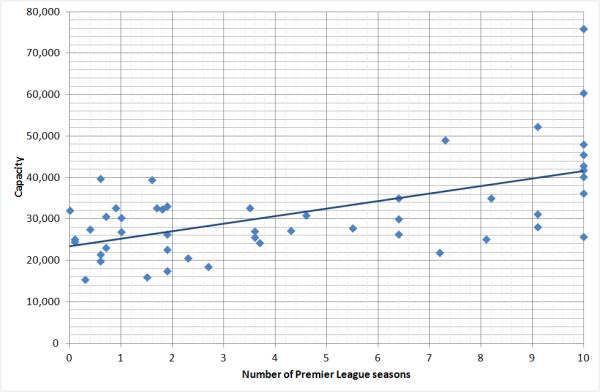

The next chart plots the capacity of the same stadiums against the number of seasons each club played in the Premier League in the last decade. We have given each Championship season a weight of 0.1 Premier League season so that the dots spread out a little more.

Some clearly distinguishable dots are for example Newcastle United (9 PL seasons and 1 Championship season), Fulham (10 PL seasons with a low capacity), and Leeds United (1 PL season and 6 Championship seasons). The dots at exactly the 1 are of course the teams that have played 10 seasons in the Championship (Cardiff and Ipswich).

The blue line shows the correlation between capacity and Premier League success, and it shows that there is some correlation, but also not a very strong number (an R2 of 34% to be precise). Note that correlation is not the same as causation.

We could argue that the clubs below the trendline have been overperforming in comparison to the size of their stadium, while the ones above the line have been underperforming. Clear overperformers seem to be Portsmouth, Wigan, Bolton, and Fulham, while underperformers are Sunderland, Leeds United, and Sheffield Wednesday. It is not very difficult to find the reasons for these cases.

We should bear in mind though, that many of the clubs that want to expand, want to move from capacities of in the 20,000s to over 30,000. Will this increase their chances much?

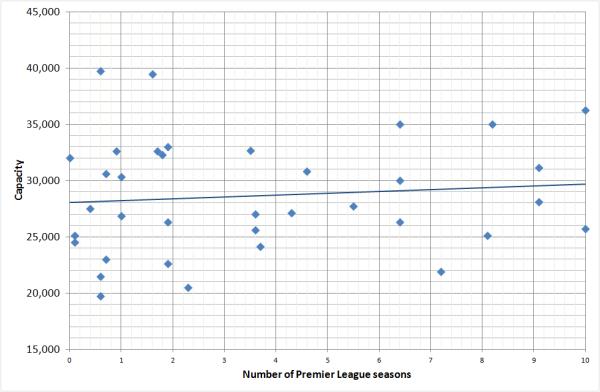

The following chart shows the same as the one above, but only for the stadium with a capacity of between 20,000 and 40,000.

There is a lot less correlation here (the R2 drops to 10%), which raises the question whether expanding to, say, 35,000 seats really helps your case in terms of playing Premier League football. Likely not very much, and it seems that instead an increase to at least 40,000 may be required.

Expanding to over 40,000 seats is a big step though, something that most clubs on the earlier list are not actively considering. The only example of a club that tried to make the leap to the big boys by building a large stadium is Sunderland.

Sunderland naturally has a rich history, but most of it was over a century ago, and when they built the Stadium of Light in the mid 1990s they were a Championship side. Making the move from the small Roker Park to a stadium of almost double the size was surely ambitious.

Has it paid off? The start at the Stadium of Light was shaky with two further seasons in the Championship, and even after the club had climbed back to the Premier League, two further relegations followed in the mid 2000s. But both times the club bounced back quickly and has been relatively safe in recent years.

In comparison, in the earlier years of the Premier League, Sunderland’s situation (stadium and attendances) was very much similar to those of the likes of West Brom, Leicester, Derby, Stoke, Crystal Palace, and Birmingham City. Sunderland now seem to be positioned slightly better than those teams, though some others (e.g. Wigan, Bolton, Blackburn, and West Ham) have done almost just as well with smaller stadiums. Still, it is not unreasonable to suggest that the club might have had a more volatile decade if it had build a smaller stadium.

If we look at the clubs that want to expand, QPR, Southampton, and possibly Nottingham Forest would be aiming for a capacity of over 40,000 seats. If West Ham gets to rent London’s Olympic Stadium, this will also be a big boost in capacity, though Boleyn Ground is already one of the larger stadiums of the list.

If various clubs go ahead with expanding capacity, this could mean that the ones left behind get less opportunity for regular Premier League football. After all, there are only 20 places in the Premier League. It may, however, also mean that few will change in this sense, which brings us to one of the big risks of increasing capacity.

Most of the clubs that are considering expanding think they can easily fill this extra capacity in the Premier League, and they may very well be right. However, if Premier League football remains an occasional thing, they may find themselves playing in very empty stadiums in the Championship.

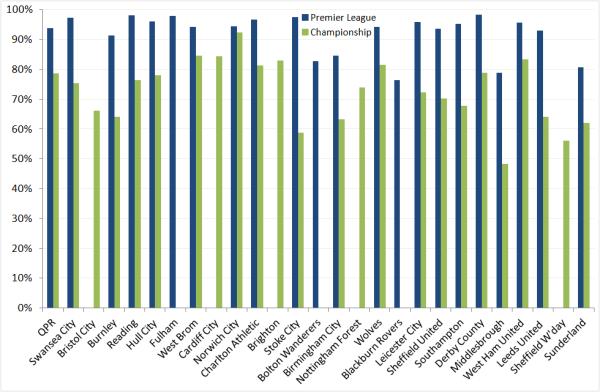

The following chart lists the average occupancy rates of some relevant teams in the last two seasons they played in the Premier League and Championship (in the last decade).

What we see here is that few clubs have problems filling their stadiums in the Premier League. We earlier found that the average occupancy rate in the Premier League is over 90%, and most of these clubs seem to easily make that. The ones that don’t aren’t currently considering increasing capacity.

So most clubs have a case when they argue that their stadium is too small for the Premier League. The problem is that most of the above teams will be spending most time in the Championship, and as we can see hardly any of them fill their stadium consistently in the Championship. Norwich is the only real exception here, though Brighton is also doing great this season.

Most clubs don’t make an occupancy rate of 80% in the Championship though, and one typically seems a ceiling of an average of 25,000 spectators a match. What’s more, attendances seem to be on the decline.

Some clubs are looking to build a new stadium instead of expanding their existing stadium, and they could legitimately expect a bounce in attendances based on the initial excitement of a new stadium. Such bounce is likely to be a lot less in the case of an expansion, but can also wear off in the long term, which is for example the case for Middlesbrough and Hull.

Some clubs have a rather healthy approach to expanding. Reading, for example, state that they do not expect much more revenue, but merely want to give more people the chance to witness Premier League football. The consequence will however be a half-empty stadium in the Championship. Is that worth it?

One should also not exaggerate the power of the Premier League to pull in crowds. Stoke, West Brom, and Wolves, for example, do not consistently sell out in the top league even though their occupancy rates are over 90%. The Premier League does attract a lot of people though, and while The Championship does very well for a non-top league, it has its limits.

Some might say that lowering prices may be able to attract more crowds in the Championship. Tickets are currently far from cheap, averaging £22.50* for the cheapest adult tickets, which gets increased to £26.50 for top category matches.

While this may be true, the problem is that matchday revenue is far more important for Championship teams than for those in the Premier League, which get a massive boost from television money. Lowering prices will therefore have a much more direct impact on the quality on the pitch, something fans may not be willing to accept.

Another option could be expanding the Premier League, something recently suggested by economist Stefan Szymanski. As adding more fixtures to an already packed football season would be next to impossible, this would mean an uneven schedule where not all teams play each other every season, and as a consequence play-offs. It is the system used in American sports, though I suspect not something likely to happen in England in the next decade(s).

The conclusion is therefore likely something most clubs have also already realised, which is to be careful with expanding a stadium. For this reason, clubs as Norwich, Swansea, and Reading first require two or three consecutive Premier League seasons before they embark on any works.

There may be the opportunity for a few more clubs to make a move like Sunderland did, but you might have to do it big, and if it does not work out, you’ll find yourself playing in the Championship in a half-empty stadium.

* Based on a random selection of 18 Championship and 2 League One teams.