This is already part five of our attendances series, having before compared the attendances of Europe’s six major leagues, and then taken in-depth looks at the attendances of the Premier League, Bundesliga, and Ligue 1. It is now the turn of the Dutch Eredivisie.

The Eredivisie’s attendances are in many ways comparable to the Premier League and Bundesliga, apart from the actual level, of course.

In our general comparison we saw that the Dutch Eredivisie averaged a total of 19,514 spectators per match, for the first time beating the French Ligue 1.

We also saw that the Dutch clubs managed to sell 91% of all seats, and to sell out 37% of all matches. Two Dutch clubs sold out all of their home matches, whereas three clubs did not sell out any at all.

There were relatively few fluctuations in attendances, though there was a definite trend upward over the course of the season after a slow start.

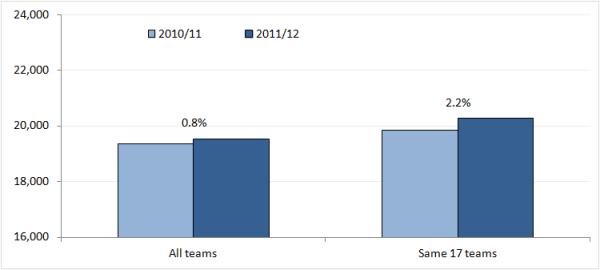

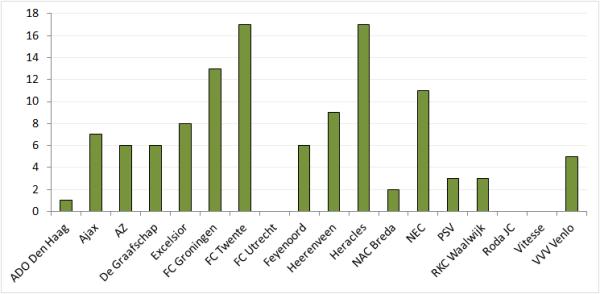

Our first analysis will look at the growth of attendances in comparison with the previous season:

We see a small increase in attendances of 0.8%. However, if we take into account that Willem II relegated and was replaced by RKC Waalwijk, and that the former tends to attract significantly more people than the latter, we see that attendances actually increased with 2.2%.

This is a very decent increase, especially if you are operating so close to full capacity (compare that with the +4.6% of the Bundesliga and -0.4% of the Premier League).

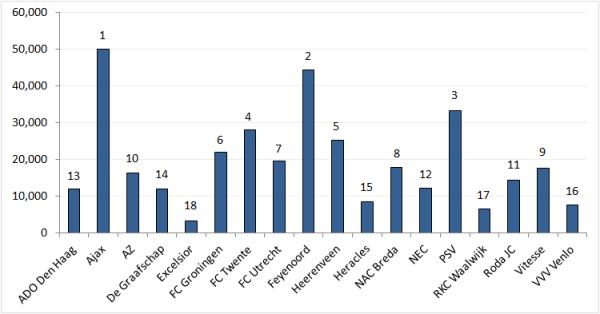

Our next chart shows how the 18 Eredivisie clubs compare in terms of attendances:

What strikes is that there is quite a difference between the clubs. Season averages range from 3,319 per match for Excelsior to 50,147 per match for Ajax. There are a few more clubs with averages of under 10,000, but then there are also Feyenoord and PSV to pull the average up again.

We actually know about the Dutch Eredivisie that the far majority (but not all) of the clubs report the number of sold tickets, but not the number of people that actually entered the stadium. Dutch clubs traditionally sell a lot of season tickets, but some clubs admit that the average percentage of no-shows is about 10% (though this tends to be lower for smaller clubs).

An extreme case happened in February during one of those very cold weekends, when Ajax reported an attendance of 47,923 for their home match against NEC (because that many people paid to get in), but in reality only 21,706 people entered the Amsterdam ArenA.

Our indication is that clubs in other leagues use similar methodologies, so there is no reason to think figures are skewed in favour of the Dutch.

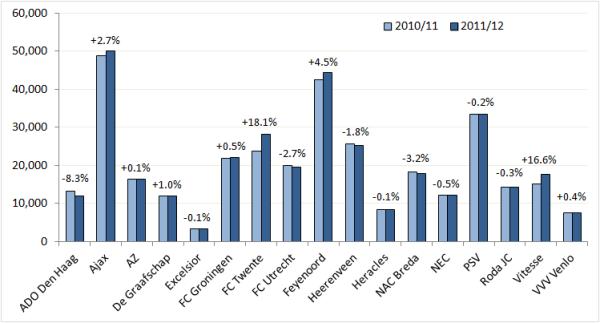

Our next analysis combines the first and second chart and looks at how last season’s club attendances compare with those of the season before:

We see that very few clubs have significant changes, often not even a change of 0.5% up or down.

On the positive end, only two changes really jump out. Those are the changes of FC Twente and Vitesse Arnhem, and they can both be easily explained.

FC Twente expanded their stadium with an additional 6,000 seats. They sold out before, and kept doing so after the expansion.

Vitesse’s attendances had been on the decline for the past few seasons due to poor results, but the club got taken-over, new funds became available, and they had a very decent season.

Feyenoord and Ajax also clearly showed signs of a good season, whereas ADO Den Haag’s attendances reverted back to normal levels after reporting a good increase the season before due to a for-them excellent season. Utrecht and NAC had little to celebrate and therefore also showed some declines.

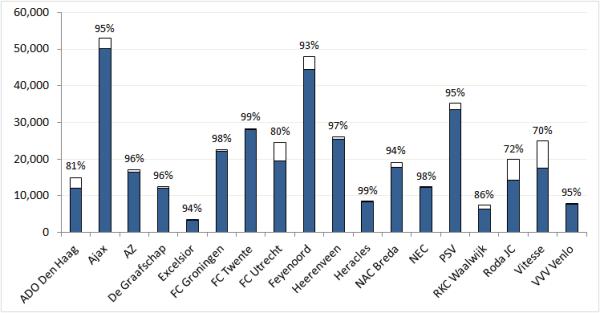

The next chart shows how well the clubs filled their stadiums:

There are really only four clubs that have a lot of free capacity, which are ADO Den Haag, FC Utrecht, Roda JC, and Vitesse Arnhem. RKC Waalwijk’s occupancy rate can also be considered to be somewhat disappointing considering the small size of their stadium.

All other clubs managed to fill their stadiums very well this season. The next chart complements the picture with the number of sold out matches (the matches at which at least 97% of all tickets were sold).

FC Twente and Heracles Almelo sold out every match, and Groningen, NEC, and Heerenveen at least half of all matches. Many clubs though, have troubles selling the tickets that are left for general sale after filling up their stadium pretty well with season tickets. Perhaps because of the club card requirements that many clubs still have.

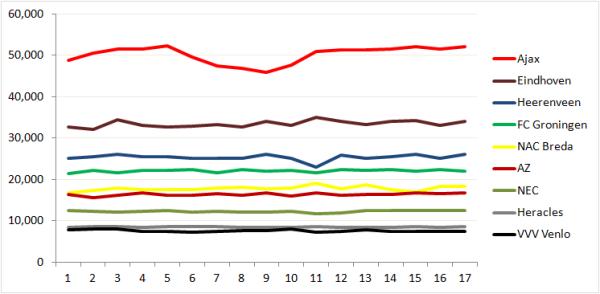

We already mentioned that attendances moved up over the course of the season, but how does this look on a per-club basis? We start with the chart of the 9 club that showed the least movement (up or down) in attendances. The 17 numbers at the bottom are the 17 home matches of each team.

The only club that had a real trend in their attendances, was Ajax. The mid-season slump reflected a similar slump in performance, but attendances picked up pretty soon after it became clear that they would compete for the title after all.

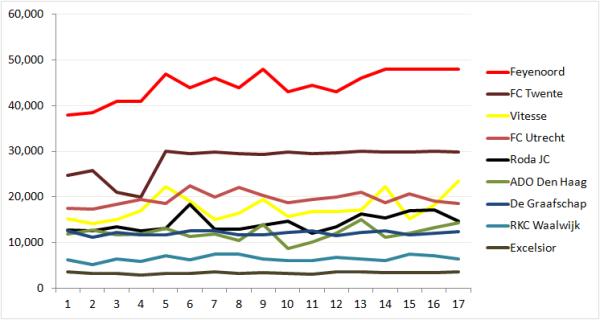

The second chart shows the development of attendances for the 9 clubs with the most movement in attendances.

Feyenoord also shows a clear trend up after fans realised they were going to have a rather splendid season. FC Twente had a changing capacity in the first months because of reparation works after an under-construction new roof had collapsed.

The club with the highest fluctuations in attendances was Vitesse (typically 19% up or down from one match to the next), followed by ADO Den Haag (19%), Roda JC (16%), and RKC Waalwijk (14%). Not surprisingly, these are all clubs with significant free capacity.

Overall, volatility of attendances is very low in the Netherlands, and they only get beaten by the Premier League in this regard.

So what does the future look like for the Eredivisie? For years we have seen a steady growth in attendances, but can they break the 20,000 mark, or even surpass the Italian Serie A?

The answer to the last question will, of course, very much depend on the Serie A. The answer on the first could very well be a yes, though it won’t come easy.

The first thing to consider is whether the two newly promoted clubs (PEC Zwolle and Willem II) will do better than the relegated ones (Excelsior and De Graafschap), and this is a definite yes. While the attendances of Willem II and De Graafschap are very much alike, Zwolle’s attendances will likely be closer to 10,000 per match than the 3,300 Excelsior attracted.

Whether there is more growth, will very much depend on how well the clubs with a lot of free capacity do. If Vitesse has another good season, their attendances have potential for more growth, as do those of ADO Den Haag and Utrecht. But they can just as well go down in case the results disappoint the fans. Feyenoord’s performance will also be critical in this.

Long-term growth will have to come from new stadiums or stadium expansions, though the Dutch clubs are definitely feeling the crisis, and finding the money to do so will not be easy.

Heracles and VVV both have concrete plans for a new stadium though, and will likely move into a new home in two to three years time.

Most of the clubs that currently fill their stadiums for 95% or more have at some time considered expanding their stadium, but few have concrete plans at the moment, and definitely not the type of expansions FC Twente has been making in the last few years. But Twente themselves have also postponed a further expansion to 40,000 seats, which they had earlier planned.

Similar expansion plans of Groningen, AZ, and PSV have long been abandoned, and NEC keeps struggling to find a way to expand the Goffertstadion. Feyenoord has plans to build a new 60,000-stadium, but it remains to be seen whether they receive planning permission and can find the funding.

It is more likely that many clubs will follow the lead of the likes of Zwolle and Heerenveen, and find creative solutions to increase capacity. De Graafschap, NAC, and VVV have already reintroduced standing in the Eredivisie, and Zwolle will do the same this summer.

As many Dutch stadiums have ditches to separate the fans from the pitch, another solution is to bridge this gap with makeshift stands. Ajax has done this in the past, and again Zwolle will do something similar. Heerenveen also had plans to do this to increase capacity of the Abe Lenstra Stadion, but plans have been postponed for the moment.

A final and even simpler way to increase attendances may be to make it easier for the neutral visitor the visit a match. Many clubs make it horribly difficult for anyone not owning a club card to visit a match, and letting go of these restrictions that seem completely unnecessary may bring more people to the stadiums.

All in all, it is not unlikely that the Eredivisie will soon break the 20,000-mark, but further growth will be slow. That is of course fine, because most clubs already own modern stadiums, are able to fill them very well, and the Eredivisie already has the highest attendances of “the rest of Europe”. Now if only Dutch clubs would become more customer friendly, you have a very fine package.