We continue with our series of the 2011/12 season in attendances with the French Ligue 1. Earlier we already analysed the attendances of the Premier League and Bundesliga, and in contrast to those, Ligue 1 does not have attendances that very much reflect the stadiums’ capacities, and therefore promises a bit more excitement.

When we compared the attendances of Europe’s six major leagues, we found that Ligue 1 ranked bottom with an average attendance of 18,870 per match, which meant that about 73% of all tickets had been sold. Attendances were also quite evenly spread, with most matches counting between 11,000 and 22,000 spectators. But that said, they were also rather volatile with many significant up and down movements. The risk of encountering a full house was not high last season in Ligue 1, with just under 6% of matches sold out.

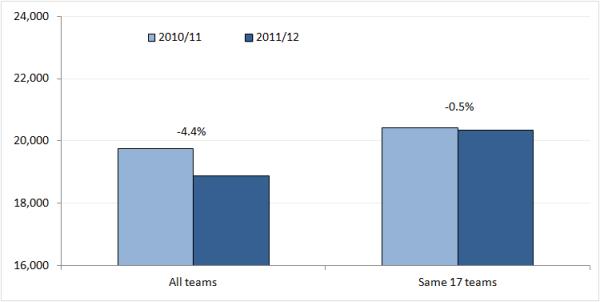

What we did not analyse is how 2011/12’s attendances compared with those of the season before, which we will show you in the next chart:

Comparing 2011/12 with 2010/11 we see a decline in Ligue 1 attendances of 4.4%. Combine that with France falling below the average of the Dutch Eredivisie, and some French may start to despair over the state of their league.

But, doing so would neglect one very important factor, which was the relegation of RC Lens in 2011. Sure, two more teams relegated (Arles Avignon and Monaco), but Lens’ 30,000+ average could not get made up for by the newcomers Ajaccio, Dijon, and Evian TG, all clubs that rank in the bottom quartile of the ranking.

If we make a clean comparison with only the 17 teams that were in Ligue 1 in both seasons, we see a small decline of just 0.5%. And when we consider that both Marseille and Saint-Etienne operated with reduced capacities this season, then things suddenly actually look quite rosy.

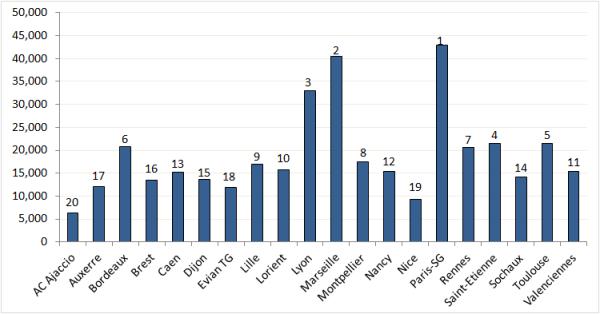

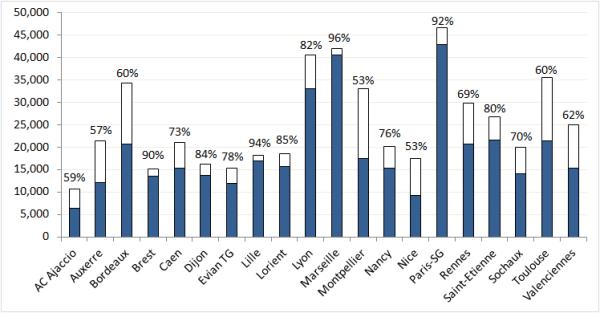

The ranking of the 20 clubs over the 2011/12 season looks as follows:

We see that, as we mentioned before, there are few clubs with extremely high or extremely low attendances, and that three-quarters of all clubs average between 11,000 and 22,000 visitors per game. The year before this was only half of the teams, so Ligue 1 has become more egalitarian.

The exceptions are Paris Saint-Germain, Marseille and Lyon on the upper side, and Nice and Ajaccio on the lower side. Especially the first place of Paris Saint-Germain attracts the attention as they only ranked fourth last year.

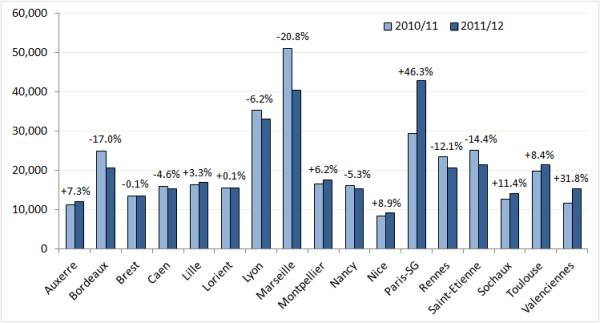

The next chart, which shows the growth of attendances per club, is arguably the most interesting of all as it shows some pretty strong movements.

First of all it is clear that Paris-SG’s ambitions and improved results have really warmed up the fickle Parisian public. Almost 50% more people saw the team play this year.

The decline in Marseille’s attendances is just as striking, but this was, as we mentioned, because Stade Vélodrome‘s capacity was capped to 42,000 due to renovation works. Without these works Marseille would likely have still topped the ranking, though its poor form would probably not have prevented some decline in attendances.

Saint-Etienne’s capacity was limited to just under 27,000, also due to renovation works, but hardly any of their attendances reached this number this year. Still, nobody likes watching football at a construction site.

More worryingly are the steep declines of Bordeaux and Rennes. Their seasons were far from spectacular, but neither awful as they both challenged for European football (though Bordeaux spent most season mid-table). Nor were their seasons much worse than the seasons before, when both recorded significantly better attendances.

Most notable among the risers is Valenciennes with a 32% increase, which can be explained by the opening of the new Stade du Hainaut. One wonders though whether club officials are really happy with the increase, or whether they had hoped that the club would record averages much closer to 20,000. They probably did considering they built a stadium with 25,000 seats.

Other attendances that look good at first sight, but make you wonder at second are those of champions Montpellier. Is an increase of 6.2% really that good for a team that has been top of the table for most of the season and has a stadium with a lot of free capacity?

The increases in attendances of Auxerre, Nice, and Sochaux are perfect examples of teams that started badly, ended up in the relegation zone, but put on a fight, set up a run of good results, and attracted a public that got behind the team. Nice and Sochaux in the end survived.

Caen would be almost the exact opposite, with a boring season that saw them in save waters around 13th place most of the season, but a sudden loss of form meant a drop in the relegation zone on the last day of the season.

So how well do French clubs fill up their stadiums?

There is not much what really catches the eye here, apart, perhaps, from the fact that especially the stadiums with a capacity of between 25,000 and 30,000 have remained very empty this season, while the stadiums with a capacity of between 15,000 and 20,000 have filled up rather well.

What’s more, many of the stadiums that have low occupancy rates were used in the 1998 World Cup. Bordeaux’s Stade Chaban-Delmas, Montpellier’s Stade de la Mosson, and Toulouse’s Stadium Toulouse stayed particularly empty. Then there are the stadiums of Nantes and Lens in Ligue 2, and if it had not been for Paris-SG’s Qatari investment and Saint-Etienne’s reduced capacity, then these clubs would have similar occupancy rates. So let’s hope that the investments in Euro 2016 do pay out in higher attendances.

Normally we would accompany the above chart with that of the number of sold out matches, but there is not much to show there. Only Marseille and Evian TG sold out more than 3 home matches, and none more than 7.

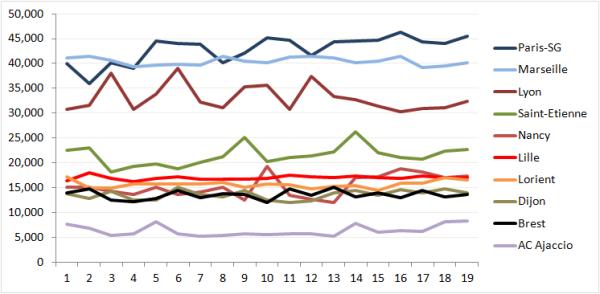

More interesting is the development of attendances over the season, especially in combination with their volatility, that is, the extent to which attendances move up and down. The first chart shows the 10 clubs with the least movement in their attendances. The numbers at the bottom are the 19 home matches the clubs played this season.

If you compare this chart with, for example, the Premier League, than it strikes that the chart of France’s least volatile clubs looks very similar to that of England’s most volatile clubs.

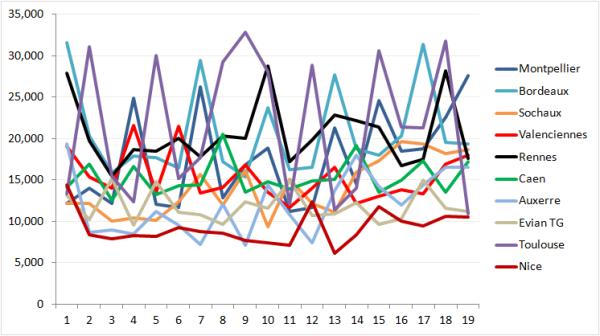

One therefore wonders what the second chart, that with France’s most volatile clubs, looks like. Well, the lines are indeed all over the place:

For example, the attendances of the clubs with the highest volatility,which are Montpellier, Auxerre, and Bordeaux, would from any home match to the next move up or down by 40% to 50%.

Actually, Toulouse’s attendances would move even more, but we have doubts about the accuracy of their published numbers. I mean, doubling attendances when Marseille comes to visit is nothing strange, but when Evian, Valenciennes, or Brest do, we become suspicious.

Other things we can witness in the charts are the mentioned-before surges of Sochaux, Auxerre, and Nice, the increasing popularity of Paris Saint-Germain, and the very late rise in attendances of Montpellier.

On the contrary, Marseille’s, Lille’s, and Lorient’s attendances were the most stable with match-to-match movements of between 2% and 6%.

So what brings the future for France? Well, a lot of interesting things.

Next season will see Auxerre, Dijon and Caen disappear from Ligue 1, and get replaced by Bastia, Reims and Troyes. It is hard to predict if this is a net benefit, but our guess is that it will likely be.

In the end, however, Ligue 1 would really benefit from the return of Lens, though it is more likely that it will first see the return of the poorly-attended Stade Louis II.

A bigger benefit though, will likely be the opening of Lille’s Grand Stade Métropole, which will become France’s largest club stadium. While it is unlikely that the club will fill all 50,000 seats for every match, it would not be too bold to suggest that attendances will move up considerably. As a result one may expect France’s average to move towards, or even over, the 20,000 again.

In the medium to long term we are very much looking at the projects that are currently in progress for Euro 2016. The obligatory upgrade of stadiums has resulted in three complete new stadiums that are currently being built (Bordeaux, Lyon, and Nice), and a further three that are getting renovated (Marseille, Saint-Etienne, and Toulouse). It is likely that after the Euros something more significant will happen to Parc de Princes.

As a result, in a few years time all of France’s top teams will be playing in a new and modern arena and it will therefore be interesting to see how this will affect attendances. Of course, they will likely go up, but it is anyone’s guess whether this will just be a, say 20%, increase, or if it will have a lasting effect on the complete league and give France a proper push to challenge with Europe’s top league.