The year 1923 was a rather uneventful one. The First World War had ended a few years ago, but the volatile years of the Great Depression were still six years away.

Sure, the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, the French and Belgian occupation of the Ruhr area, and the peak of hyperinflation in Weimar Germany were hardly unnoticeable, but for that period in time, it was a rather quiet year.

That is, if we talk about politics, war, and economics, because if it comes to the topic in which we specialise, football stadiums, one can argue that it was a magical year, perhaps the most ever.

We invite you to have a look at our timeline of stadium openings, and some things will likely attract your attention: obviously a lot of new stadium openings in recent years, the almost all-British 19th century, hardly any activity during both World Wars, and then some periods with more openingd and some with less. One year though, clearly jumps out in terms of the number of stadium openings, which is 1923.

At least nine new stadiums opened in Europe that year, some arguably more important than others, but it gets more interesting when we start scrolling up and down and realise that the year was very much defining for what had happened in the years before and what was going to happen next.

We will walk you through the year of 1923, the stadium openings, and relate these to their place in stadium history.

18 February 1923 – Estadi de Sarrià, Barcelona

The first club to open a new stadium in 1923 was Espanyol. Plans for the new stadium had been ambitious, and were in no doubt fuelled by the opening of Barcelona’s Camp de Les Corts in May of the previous year.

The vision was a stadium with 40,000 places, much more than the 22,000 of their rivals, but reality soon set in when a lack of funding meant that 10,000 was all that was possible for then.

Still, the city of Barcelona was now in the possession of two proper concrete stadiums, and it was not just Barcelona that witnessed new stadium openings, because we will encounter various more later in the year.

23 April 1923 – Wembley Stadium, London

These were special days, because in the span of just 5 days two of the most iconic stadiums the world has known opened.

On the 18th of April 1923, the original Yankee Stadium opened in New York City, and then 5 days later across the pond the first Wembley Stadium.

Wembley Stadium was the icing on the cake of three decades of stadium construction, and England now finally had a venue to challenge the much-larger Scottish stadiums.

This had been more of an accident then purpose though. The stadium had been built for the British Empire Exhibition, and while it soon after opening hosted the FA Cup Final (the famous “White Horse” one where over 200,000 people turned up), no legacy plans had been made, and after the summer it became clear that the stadium was not financially viable and it got close to being demolished.

It was then that savvy local entrepreneur Arthur Elvin bought the stadium and managed to slowly turn it into England’s leading venue. He brought football back in, but also other sports and greyhound racing, and would later help attract such events as the 1948 Olympics.

13 May 1923 – Stadium Metropolitano, Madrid

Barcelona now had two new stadiums, so it cannot have come as much of a surprise that Madrid was about to follow. It was not Real Madrid though, that opened a new stadium, but rivals Atlético were the ones moving home.

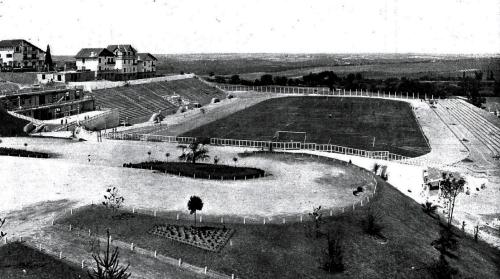

While Real was already the most successful club of the city at that time, Atlético were ambitious and regularly challenging them in the then still regional league. They had outgrown their small stadium in the south of the city, and therefore decided to move to a new home up north.

The stadium was built at a complete new site near the last station on Madrid’s newly opened first metro line.

The great asset of Stadium Metropolitano were the natural earth banks that surrounded the pitch, which, together with a proper main stand, could hold about 25,000 people. Another 20,000 could witness the game from elevated places around the ground.

Just as in Barcelona, the new ground of Atlético prompted rivals Real to also start making plans to build a new stadium. Their Campo de Chamartín would open in the next year.

20 May 1923 – Estadio de Mestalla, Valencia

Another new Spanish stadium, and one that actually still exists today. There is, of course, a similarity in the story of all these new stadiums in Spain, which is that all the clubs encountered a rapid growth in fans and were therefore almost forced to move to a bigger ground.

These bigger grounds were also better, often replacing old wooden structures with new concrete stands. Mind that they were still very modest in comparison with the stadiums of today, or those that existed on the British Isles in those years.

For example, the 1923 Estadio de Mestalla could only hold 17,000 fans, many of those only standing, but it was a big development for Spanish football in comparison to where they came from.

Many of these stadiums got further expanded in the following years until the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s brought everything to a halt and often even caused significant damages.

The next wave of development then started in the mid-1940s with Estadio de Riazor and Estadio Santiago Bernabéu, but would be spread out over much more years and last until the late 1950s.

There were actually more Spanish stadiums opening in 1923, for example Estadio Torrero of Real Zaragoza, which had a similar capacity as Mestalla, and Villarreal’s Estadio El Madrigal, though the club had just been founded and the ground was not much more than a pitch and some basic stands.

25 August 1923 – Maine Road, Manchester

While we just presented Wembley as the highlight of decades of English stadium building, one could also argue that Maine Road deserves this title.

Maine Road replaced Manchester City’s previous ground Hyde Road, which had become too small and had gotten heavily damaged in a fire. The architects had envisioned a stadium with a capacity of 120,000 that could challenge the large Scottish grounds, but plans were scaled back and 85,000 was all that was left.

Still, this meant that Maine Road was then the largest club-owned stadium of England, all built from scratch. The stadium consisted of one large covered main stand and large open terraces on the other sides, and would slowly get further developed over the years, though never further expanded.

The year 1923 is so significant for English stadiums, because Wembley Stadium and Maine Road would be the last large newly constructed stadiums in England until the 1990s. That is, the under-construction Selhurst Park would open in January of the next year and Carrow Road would get built in the 1930s, but these stadiums did not have the grandeur of those of England’s big teams.

The contrast with other countries was sharp, as we just saw that in, for example, Spain, clubs had only just started building new stadiums. This was no different in other parts of the continent, which highlights what a defining year 1923 was.

Did this mean that all British stadiums had already reached the state in which they would remain for the next 70 years? No, because most of the clubs were still busy redeveloping and building new stands, which they would continue to do so in the 1930s and in the post-War years.

Ironically, neither Wembley Stadium nor Maine Road had been designed by the architect that placed his mark on so many stadiums of the times: Archibald Leitch.

Leitch, who had started designing factories before he rolled into football, was one of the most in demand architects of the time and has had a lasting impact on stadium design. He was, however, not asked to design any of the two largest stadiums. Simon Inglis later attributed the fact that Wembley Stadium had such a “lousy” design to the fact that the arrogant architect of the stadium had ignored Leitch’s advice.

The year 1923 proved to be quite an important one for Leitch as well though, as his signature achievement was built throughout most of the year. Villa Park‘s Trinity Road Stand, later demolished, opened just after the year had ended. One of his other important works, the main stand of Ibrox, would open a few years later.

16 September 1923 – Müngersdorfer Stadion, Cologne

Germany was a country in turmoil in the early 1920s. It had just lost the First World War and the restrictions of the Versailles treaty had brought a cloud of pessimism over the county.

One of the objectives of building Cologne’s Müngersdorfer Stadion was therefore to instil some new pride in the country. The added benefit was that it provided work for a total of 15,000 labourers.

Müngersdorfer Stadion was of a different scale than the stadiums that had been built in the previous decades in Germany. Until then, the largest stadiums of the country were still rather simple affairs, that often consisted of wooden stands and earth terraces, and which could hold a maximum of 30,000 to 40,000 people.

More modern concrete variants had already been built in the year before in Leipzig and in the same year in Dresden, whereas Fürth’s Sportplatz Ronhof had developed into the largest stadium of southern Germany.

Müngersdorfer Stadion, however, was of a different scale. It could officially pack 80,000 spectators, formed part of a larger sportpark of venues, and an estimated 300,000 showed up at the opening. It immediately earned itself the nickname “mother of all stadiums”.

The stadium would initially hardly get used for football though, as Köln stayed at their old ground and it would take until 1927 for the first international to be played at the ground (Germany vs Holland).

However, the stadium did pave the way for a new generation of large German football stadiums. In the rest of the 1920s, it was followed by the Rheinstadion, Waldstadion, and Nürnberg’s Städtisches Stadion, while the Wankdorfstadion opened in nearby Switzerland.

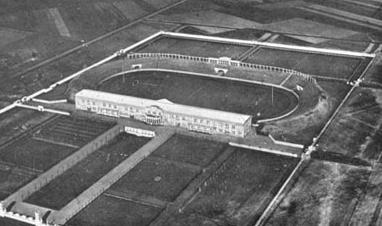

16 September 1923 – Stadio Ennio Tardini, Parma

While the opening of Müngersdorfer Stadion in Germany was a defining event, this was certainly not the case for Stadio Ennio Tardini.

It was a modest oval-shaped stadium with athletics track and a small covered stand, which was probably quite right for the status of Parma at that time.

Italy’s big clubs, however, were also not yet playing in large stadiums, and it would take a few more years for them to do so.

San Siro was the first to open in 1926, but stadium-construction really took off when the fascist regime had established themselves in power and started building prestigious stadiums, which led to the (start of) construction of such stadiums as Stadio Olimpico, Stadio Comunale, and Napoli’s Stadio Partenopeo.

1 November 1923 – Bosuilstadion, Antwerp

Outside the big football countries, there was also new stadium activity in Belgium. Four years earlier, Antwerp had already opened one new stadium, the Olympic Stadium, and the new Bosuilstadion was now added to that.

The Bosuilstadion would become one of the most iconic stadiums of the low countries over the next years, and would be the standard playing venue of the regular Belgium versus Netherlands internationals that were played in those years. The hectic atmosphere subsequently earned the stadium the nickname “hell of Deurne”, Deurne being the area of Antwerp the stadium was located in.

De Bosuil paved the way for further stadium developments in the low countries in the next decade, which included the Amsterdam Olympic Stadium, Ajax’s De Meer, the Heysel Stadium in Brussels, and later De Kuip.

In conclusion, the combination of the first wave of British stadium construction reaching its peak and the foundation of a new generation of larger concrete stadiums on the European mainland made 1923 quite the extraordinary year.

More fruitful periods of stadium building obviously followed, and in particular the 1950s and mid 1990s turned out to be quite significant, but never was there one particular year as magical as 1923 was.